Oregon Art Beat

Lillian Pitt, Lindsey Fox, Hunter Noack

Season 26 Episode 4 | 29m 4sVideo has Closed Captions

Mixed media artist Lillian Pitt, watercolor painter Lindsey Fox, pianist Hunter Noack.

Renowned contemporary artist Lillian Pitt creates art for public installations and galleries in clay, glass and mixed media informed by the stories and iconography of her ancestors. Lindsey Fox’s watercolors transform Oregon landscapes into abstract patterns of art. Classical pianist Hunter Noack and friends haul a 9’ Steinway grand piano to some of the most remote, beautiful places in Oregon.

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Lillian Pitt, Lindsey Fox, Hunter Noack

Season 26 Episode 4 | 29m 4sVideo has Closed Captions

Renowned contemporary artist Lillian Pitt creates art for public installations and galleries in clay, glass and mixed media informed by the stories and iconography of her ancestors. Lindsey Fox’s watercolors transform Oregon landscapes into abstract patterns of art. Classical pianist Hunter Noack and friends haul a 9’ Steinway grand piano to some of the most remote, beautiful places in Oregon.

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Oregon Art Beat is provided by Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer Care Foundation Endowed Fund for Excellence... and OPB members and viewers like you.

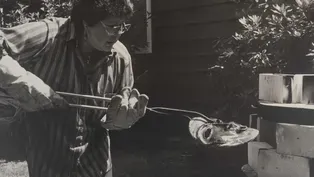

Funding for arts and culture coverage is provided by... [ ♪♪♪ ] [ ♪♪♪ ] LILLIAN: I'm making the Star People.

They're not really people.

They're kind of creatures and everything.

The stars brought these people to us to help us live better and be kind and thoughtful to each other.

And so that's my Star People with their wonderful images and projections that only I know, you know.

At a sculpture meeting, they were trying to figure out who to choose to do what.

I said, "You know, I had a dream about this big totem."

MAN: She said, "Don, I had a vision last night, this dream that we would find a log that came out of the St. Helens explosions and had been-- gone down the rivers and ended up at the ocean and was kind of salt-cured.

And if we got this log, we could bring it in as a marker, almost as a totem at the center itself.

If we were able to take metal pieces and wrap them around this pole that indicated the life of a salmon from the egg up to the final dance at the top of the pole.

And in a way," she said, "it parallels with students, that they come in almost as an egg and they leave as something that will go on to other places and doing other things."

LILLIAN: One of the things that really inspires me to continue with my public artwork is to let people know that we're still here.

There's Indian women out there making artwork whose interest is to educate the public.

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ birds chirping ] I was born in Warm Springs, Oregon, so Warm Springs Indian Reservation, in 1943.

I must've been about 4 or 5, watching my elders' beadwork.

And my mother did beadwork, and then she made moccasins, so I just-- it was always there.

And my dad was very creative.

He had a beautiful voice and just could sing.

He was a tenor.

Then he had a baseball team, too, so the Indians and the white guys always fought.

You know, they ended up fighting each other after every single game.

It was no fun.

I moved to Portland the day after high school graduation.

I just had enough of the prejudice in Madras.

She actually came to town as a beautician, and because she had such a bad back problem, she couldn't do that anymore, so she turned to art.

That's what changed my life, touching clay.

I just love touching it, feeling it, smelling it, in all its stages, from moisture to dryness to fire.

It just seemed to tie me to Mother Earth.

This I don't want to ever let go of.

[ ♪♪♪ ] And I thought, "Well, I've found my way, but I don't know what to do with it."

I said, "I gotta go talk to my elders."

I went to Warm Springs and I said, "Now, who am I?

Who are my people?

And where are we from?"

They told me that we came from the Columbia River Gorge and we had lived there for thousands and thousands of years, until the mid-1800s.

The government moved the Washington people to Yakima and they moved the Oregon side to Warm Springs, and I thought that's where we were always from.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I said, "I keep seeing this image."

She had these big eyes and she was huge, and I said, "What does that mean?"

They said, "Her name is Tsagaglalal, 'She Who Watches.'"

And there was a story that went along with it.

And I'm sitting there listening to all these beautiful words these elders were telling me.

I just felt like, "I've been found.

I've found myself."

When I did finally get to see She Who Watches, it was a profound sense of identity and strength that no one can take away from me ever.

And that has carried me for 40-some years in this business.

I got to know Lillian a number of years ago because one of the main goals of the Friends of Fort Vancouver is to help reintroduce Indigenous heritage to this historic site.

So we have progressed from there, and we have one of the largest collections of Lillian's work here at the site.

I would say there is no line between the stories and Lillian's work, and that's probably why Lillian is just as excited about her artwork in a very non-egotistical way as anyone else, because there's the story, right there, in this little otter's face that emerged out of clay.

It's as if it's the first time she's seen it, and so it's something that flows through Lillian.

It is creation in many ways.

[ ♪♪♪ ] MAN: You know, when I first moved to Portland in the mid-1980s, one of the things that surprised me is, I knew there were Native people here, but driving down the streets, you don't see any Native art.

It's like we were erased.

And probably about three or four years ago, we started doing more affordable housing development right here in this area.

I wanted to make sure that these buildings looked and felt Native.

So I wanted to make sure that when you drove down the street, it was going to be a Native building.

And the first person I thought of was Lillian.

If you look at what she's doing, she's using modern techniques but on very organic materials-- basalt rocks, etchings, engraving stones and images into these incredible pieces of just earth.

One of the great gifts we have from Lillian is these monumental works of art.

[ ♪♪♪ ] It reminds people that Native people were here and we're still here.

DONALD: What Lillian does is she places herself in the current timeline, but as guardian of the past.

But I also feel as a visionary for the future.

LILLIAN: You have to be resilient.

You have to be flexible.

And you have to be forgiving.

From knowing all these wonderful people I've worked with in the past and who I'm working with now has just made me feel like I have a very blessed life.

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ birds chirping ] When I'm in nature, I really love finding patterns.

I was always really obsessed with the environment around me.

It was always a visual fascination with the natural world.

And also I just love being outside.

My name is Lindsey Fox, and I do watercolor painting that primarily focuses in landscape and abstraction.

In nature, it's never the exact same thing twice.

The way that I work with watercolor mimics that.

What inspires me are rocks, mountains, craggy peaks, basically just anything that includes pattern.

I don't really like when things look exactly how they're supposed to.

Often, you'll see that vista.

You won't necessarily see the rock that I'm most intrigued by or the light or the color relationship.

Abstraction allows me to exclude what I don't really care about and include what I really do.

What attracts me to this particular spot is not only the waterfall but mostly the rocks that are around it.

So that's really the energy that I'm trying to capture here.

I grew up in northern Michigan, in the lower part of the Mitten, on a peninsula that basically was a lot of farmland, a lot of waterfront, a lot of dunes.

That kind of fostered my love for patterns and patterns in nature.

My dad is a sculptor.

I've always really been drawn to abstraction because of the way that my dad's work is made.

In our work, you'll often see our color palettes really relate.

Abstraction is so much harder than just representing something, because you're taking all of these different elements and you're deciding what happens.

I moved to Portland in 2013.

It was right after I graduated from college.

I really wanted to explore the landscape.

It's so inspiring that it's just mind-blowing.

And I feel much more supported in the arts here.

I began working at Nike in 2015 as a contractor.

It was a great job, but there was a point where I was starting to not be able to pursue creative projects in my own work.

I started to feel like in order to push myself with my own work, I needed to let that other full-time job go.

Eventually, this kind of eclipsed it.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I moved into a larger studio in 2021, and I just realized that I wanted to be here more and I wanted to paint more.

Working for yourself, there are a lot of anxieties that come with that.

I grew up with two artists as parents, and so it's terrifying doing your own thing.

[ ♪♪♪ ] Watercolor is really soft, and when you layer it and layer it and layer it, it becomes really bold.

At the beginning, I always paint.

Working with a big brush, that's kind of how I create the composition.

I'll start to add in more layers... and include more elements.

Once that composition is resolved, I'll start to think about how I want to add ink.

It's a really meditative process.

[ pen tapping on paper ] Pen and ink is almost kind of a way of cheating watercolor.

It's a way of adding more texture and more points of interest.

I decided that I was starting to care less about what the landscape looked like in my painting and more about individual pieces in the landscape.

I didn't care that it looked like what it was supposed to look like.

I cared that it felt like what I saw.

[ ♪♪♪ ] When I'm in a flow state, if I make a mistake, it doesn't matter-- it's a part of it.

That flow state is really important because I'll discover a different mark that interacts with the piece in a different way that I didn't notice or that I didn't plan.

Painting these is like experiencing little blips of nature rather than bigger moments.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I really want to create a body of work that speaks to the concepts that I want to talk about.

[ birds chirping ] I want to encourage people, while they're outside in nature, to not have it just be about what's at the end but have it be about that experience and what that feels like and what that does for you.

[ piano playing classical music ] MAN: The piano movers are gonna take it off.

They'll just roll it up here.

Keys here?

Yeah.

Piano up?

Mm-hmm.

And then guests this way out?

Yeah.

Okay.

[ playing classical music ] BRUCE BARROW: Classical pianist Hunter Noack had an idea: perform 25 outdoor concerts in some of the most remote and beautiful places in Oregon.

He calls this project "In a Landscape."

HUNTER: There's something about a 9-foot American Steinway concert grand piano that I just knew that I wanted the biggest piano out in these magnificent landscapes.

Of course, nobody that owns a 9-foot Steinway is gonna let me borrow it to take it to Fort Rock and Pendleton and Astoria and up and down through coastal ranges, sitting in, you know, 90-degree heat and then overnight near freezing temperatures.

So Jordan Schnitzer came through, and he got a beautiful 1912 Steinway D for the project.

Basically this whole project is kind of like a way for us to just camp... and make music.

In really cool places.

In really cool places.

[ piano and violin playing classical music ] Growing up in Sunriver, I grew up hunting and fishing with my dad and kayaking on the river, and we were just always outdoors.

I love performing and I love classical music, but there aren't many classical musicians who also love to hunt and fish.

And I'm not -- you know, I'm not out here hunting and fishing from my piano stool, but it... the concept just kind of came from this desire to bring those two things together, being outdoors and playing classical music.

We've been talking about just this kind of concept now for like a couple of years.

And it's kind of like a constant conversation.

It was months of kind of going back and forth between do we make the trailer enclosed or do we keep the piano on its legs?

[ laughs ] Keep it going.

Ho!

Hang on.

Let me just check it.

I mean, it's kind of nice there.

It's actually centered within the trees and the... [ playing classical music ] That may be a new jack design I just stumbled upon.

[ laughs ] Ready?

HUNTER: Only in the last six months did I start working with a couple friends.

None of us are really professional engineers, but we came up with this plan that we thought, "That should work."

And then at a certain point, a few months before the show, my friend Noam said, "At some point you're just gonna have to take the risk and try it," so that night I ordered these hydraulic lifts... my friend Noam came over, and we lifted the piano up, took the legs off, lowered it down, and that was kind of our testing.

And the next time we did that, it was on the trailer.

My friend Will, he's the stage manager, and he's borrowed his dad's pickup truck, which is an awesome truck.

[ chuckles ] The piano's actually without its legs, sandwiched between two layers of foam, and we just hitched the trailer up to the truck, and it's a pretty smooth ride for the piano, considering it's just on a flatbed trailer.

I just bought it on craigslist.

[ laughs ] [ playing classical music ] It works.

And you'll see the power light come on, and then press and hold.

HUNTER: As I thought, okay, well, I can bring a piano outside, that's not a problem, but how will it sound?

Because the sound just kind of doesn't bounce off anything.

It just evaporates.

So what we do is we mike all the instruments, it goes into a mixing board, and we had an amazing sound engineer, David Lindell, who mixes all the sound, artificially adds reverb to make it sound like we're performing in a chamber hall.

And that's the sound that's broadcast in real time to the audience.

But they have the freedom to wander 200 meters away with wireless headphones and still have the sound of a concert hall.

The ideal scenario is that the audience is not necessarily paying attention to me but that my performance is providing a soundtrack to their experience of the landscape.

We have guest performers at most of the shows.

I play sometimes with a couple amazing musicians from Portland, Pansy Chang and Nicholas Crosa and Nelly Kovalev, and then wherever possible I feature a local young artist.

So here in Eugene, we have Karlie Roberts, who was a winner for the Eugene Symphony Young Artists competition.

[ birds calling ] [ indistinct conversation ] My mom ran the Sunriver Music Festival, and every year they would have a Van Cliburn medalist come and be the soloist with the orchestra.

And those pianists were the heroes.

They would sort of waltz in and be fabulous and play with the orchestra, and those were the celebrities of Sunriver.

So I think that's partially what drew me to the piano.

When I was 14, I decided to go to Interlochen.

That's when I really started taking music more seriously.

It kind of brought out this competitive nature in me that I like.

I liked being the last one in the practice room, and I liked, you know, getting up at 6:00 and going and doing my Hanon exercises.

And it was nice to be around other kids that were my age that were taking music so seriously.

Studied with John Perry in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California, and then I got my master's in London at Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

I mean, there are so many sites across Oregon that I fell in love with when I was scouting.

It's really fun.

It's so great to wake up in the morning and... and just be outside with a team of people, and we're all working towards something and we have offices like this.

[ audience applauding, cheering ] Support for Oregon Art Beat is provided by Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer Care Foundation Endowed Fund for Excellence... and OPB members and viewers like you.

Funding for arts and culture coverage is provided by...

Video has Closed Captions

Classical pianist Hunter Noack and friends haul a Steinway Grand piano to remote places in Oregon. (11m 5s)

Video has Closed Captions

Renowned contemporary artist Lillian Pitt creates art for public installations and galleries. (9m 2s)

Watercolor painter Lindsey Fox transforms Oregon landscapes into abstract patterns of art

Video has Closed Captions

Lindsey Fox’s watercolors transform Oregon landscapes into abstract patterns of art. (8m 43s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipOregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB